This is one of the longest-running and still-unresolved questions in science. There are hundreds of competing biological aging theories and no scientific agreement that any one of them is correct. There is not even any agreement on the fundamental nature of aging. Is aging something that happens to your body as a result of forces of nature or is aging something your body does to itself like growth or puberty? It turns out that the choice of aging theory is almost entirely driven by one’s choice of evolutionary mechanics theories or the theories describing how the evolution process operates.

This is one of the longest-running and still-unresolved questions in science. There are hundreds of competing biological aging theories and no scientific agreement that any one of them is correct. There is not even any agreement on the fundamental nature of aging. Is aging something that happens to your body as a result of forces of nature or is aging something your body does to itself like growth or puberty? It turns out that the choice of aging theory is almost entirely driven by one’s choice of evolutionary mechanics theories or the theories describing how the evolution process operates.

Observations Concerning Lifespan and Senescence

There are a number of observations that are essential to modern aging theories. Because aging theories are essentially subsets of evolution theory, and because evolution theory applies to all living organisms, scientifically credible aging theories need to consider multi-species observations about aging and internally determined lifespan such as:

- Lifespans and senescence vary greatly between species. Mammal lifespans vary over more than a 200 to 1 range between some whales (> 200 years) and some mice (< 1 year). Fish lifespans vary over a range of more than 1300 to 1.

- Symptoms of aging tend to be similar but not identical between related species. Dogs and humans, even though their lifespans differ by about a factor of seven, suffer from very similar symptoms of aging like cancer, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, mobility and sensory deficits, etc.

- Internally determined lifespan resembles an evolved trait: It varies somewhat between individuals and to a much larger degree between species.

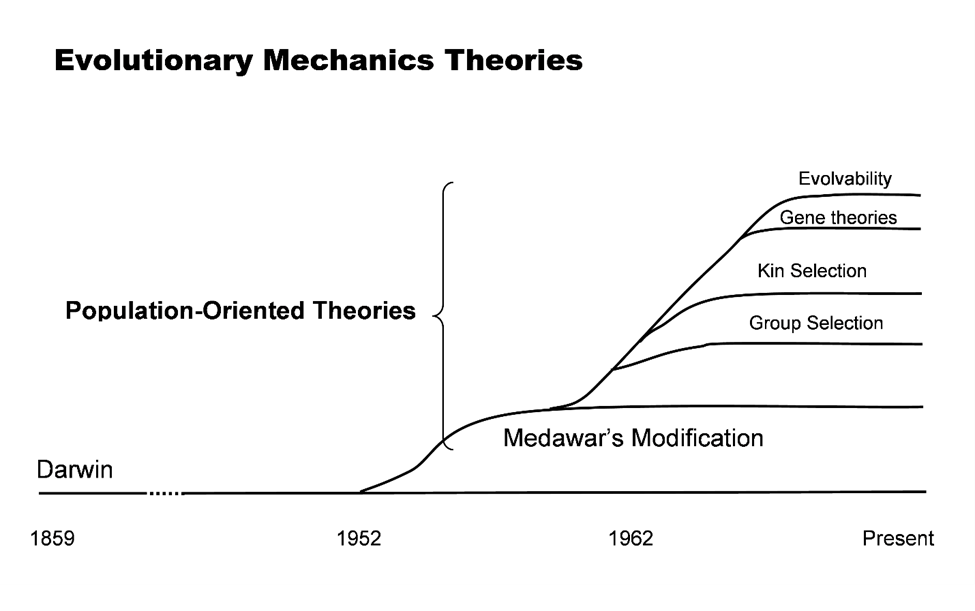

There is extremely good scientific agreement on most aspects of Darwin’s evolution theory as described in Darwin’s book of 1859 and currently taught. However, despite the more than 150 intervening years there is still disagreement regarding arcane evolutionary mechanics details. Specifically, does the evolution process operate to benefit individual members of a species population or does it operate to benefit a population of individual members of a species? This obscure detail might well appear to be trivial and in maybe 99 percent of observations of organism traits makes no difference. This is because evolved inherited organism design characteristics or traits that benefit the ability of an individual to survive and reproduce also benefit the ability of a population of those individuals to avoid extinction and grow. Aging is one of the exceptions as described below.

This obscure detail is crucial to the aging theory issue. A high-school biology student could tell you that Darwin’s theory says that the evolution process causes organisms to acquire traits that cause possessing individuals to live longer and breed more than non-possessing individuals, and further that aging obviously does not cause an aging individual to live longer and breed more than an otherwise identical non-aging individual. On the other side, some theorists have now suggested at least a dozen ways that aging helps a population despite being adverse from an individual’s viewpoint and, so far, there has been no scientific disagreement with any of these ideas. Therefore the population vs individual issue is the controlling issue for aging theories as well as some other observations. The evolutionary mechanics issues have resulted in four classes of aging theories:

Simple Deterioration or Damage Theories

Simple deterioration theories suggest that aging is simply the result of the same sort of processes that cause gradual deterioration in non-living objects and systems. Physical processes include mechanical wear and tear, and micro-injuries. Perhaps aging results from nuclear background radiation. More chemistry-oriented causes might include oxidation, damage from free radicals, telomere shortening, random damage to DNA, etc. These theories are still popular in the general public: “We wear out” (like automobiles or sewing machines or exterior paint). There is little scientific disagreement with the idea that deteriorative processes could be parts of the mechanisms that cause aging.

However, major problems quickly became apparent in the bioscience community:

- Living organisms obviously possessed many maintenance and repair functions that acted to prevent or reverse damage. Wounds heal, shed hairs are replaced, worn nails and claws regrow, blood and skin cells are continuously replaced.

- Living organisms were capable of evolving changes in their designs that act to reverse or prevent deterioration.

Obvious question: If aging is the result of simple deterioration processes, why didn’t organisms evolve ways to overcome those processes as they had already demonstrated? This problem led to the fundamental limitation theories.

Fundamental Limitation Theories of Aging

As described above, Darwin’s evolutionary mechanics concept suggests that the force of evolution is toward developing non-senescent species. Individual members of a species that do not possess any internal limitation on their reproductive lifespans would be able to live longer and breed more than competing senescent individuals. Obvious question: Why, given billions of years of evolution, are there still senescent species? Obvious answer: a longer lifespan is physically or chemically impossible because of some law of physics or chemistry. Of course there are books full of laws of physics and chemistry and human aging is a gradual general deteriorative process superficially similar to aging in machinery and exterior paint. The second law of thermodynamics (entropy) is often cited in connection with aging. Today, because of their good fit with Darwin’s mechanics and human aging, fundamental limitation theories are still popular with the general public and some physicians.

However, fundamental limitation theories utterly fail to explain multi-species observations about aging. Why would a 50 Kg dog be seven times as affected by some law of physics or chemistry as a 50 Kg human? Why would a parrot live six times longer than a crow? Articles about fundamental limitation theories typically ignore non-humans and target people who are mainly interested in human aging.

Aging Theories that Propose a Limit to Lifespan Benefit

In 1952 Nobel-prize-winning biologist Peter Medawar proposed a modification to Darwin’s mechanics to the effect that the evolutionary benefit of living longer and breeding more declined with age in a species-specific and population-specific manner, and further that internally determined lifespans needed by members of a wild species population depended on external circumstances such as predation, food supply, and habitat surrounding the population as well as internal traits such as age-at-puberty and other reproductive behaviors. Evolution is all about competition and “survival of the fittest” under wild conditions. We can easily imagine that there would be a species-specific age at which virtually no individual members of a population would remain alive because of external causes of mortality such as predators, infectious diseases, harsh environment, lack of food, or any of the myriad other causes of death in wild organisms. Consequently there would be little evolutionary motivation to develop the internal ability to live longer than a species-specific age. A population of aging individuals might be essentially as successful as a population of otherwise identical senescing individuals. This led to a family of modern non-programmed aging theories to the effect that each species only needed the internal capability for achieving a particular internally-determined lifespan and therefore only evolved and retained the ability to live that long. These theories provide a much better match to multi-species observations and are currently popular in the gerontology community.

However, subsequent (1957) widely accepted analysis by George C. Williams suggested that the deteriorative effects of aging occurred too early in life to have no negative effect on a population. Deterioration in strength, speed, and sensory acuity would affect an organism’s ability to survive and compete well in advance of the age at which most individuals would be dead from external causes and thus negatively affect survival of the population. Wild animal studies confirmed Williams’ analysis. This led to the conclusion that senescence must create a benefit for a population that offset its negative effects.

There are multiple competing theories that propose different solutions to this problem including the mutation accumulation theory, the antagonistic pleiotropy theory, and the disposable soma theory, and no agreement as to which is correct. Proponents of programmed aging (below) have described many logical and observational issues with each of these theories. Articles about mammal aging theories based on Medawar’s and Williams’ concept typically ignore non-mammals.

Programmed Aging Theories

Programmed aging theories are based on modifications to Darwin’s mechanics (and extensions to Medawar’s ideas) to the effect that aging, although adverse to individuals, benefits populations and that therefore species evolved biological mechanisms that internally limit their lifespans. Aging is an adaptation that serves an evolutionary purpose just as eyes, ears, and toes serve a competitive purpose in a wild population. Although programmed aging was first formally proposed in 1882, it was largely dismissed as obviously scientifically ridiculous because of the gross and direct conflict with Darwin’s mechanics until about 2002. Various analyses of Darwin’s mechanics confirmed that of the student: Darwin’s mechanics concept does not support population benefit or dependent programmed aging theories. The idea that we possess what amounts to an evolved suicide mechanism or “biological self-destruction clock” that limits an individual’s ability to survive and reproduce grossly conflicts with the nature of evolution as most people understand it.

However, a number of developments (and non-developments) have exposed additional issues with Darwin’s mechanics concept that specifically support population benefit and programmed aging:

- Despite more than 150 years of effort theorists have been unable to produce an aging theory that is fully compatible with Darwin’s mechanics and simultaneously even semi-plausibly explains multi-species aging observations. Modern non-programmed (non-adaptive) aging theories are based on post-1952 modifications to Darwin’s mechanics that are more population-oriented.

- In addition to senescence, other observations conflict with Darwin’s mechanics. These include sexual reproduction, individually adverse mating rituals and other behavioral observations such as animal altruism, and existence of apparently non-aging species. This led to the post-1962 development of multiple population-oriented mechanics theories including group selection theories and evolvability theories.

- Genetics discoveries have exposed multiple issues with Darwin’s mechanics and support population-oriented mechanics and programmed aging theories. More generally, genetics discoveries suggest that the evolution process is much more complex than previously thought.

- Some very explicit and obviously programmed suicide mechanisms have been discovered in non-mammals such as octopus and roundworm. Genetically engineered roundworms have been produced that live ten times as long as the wildtype!

Current Status of Aging Theories

The present situation is that current published science no longer supports the idea that programmed aging is impossible. The academic gerontology community still largely supports non-programmed theories based on Medawar’s/ Williams’ modifications to Darwin’s mechanics because such theories provide a better fit to multi-species observations than the fundamental limitation theories while not being so obviously incompatible with Darwin’s mechanics. Commercial entities (e.g. pharmaceutical companies) have begun to make major investments in research based on programmed aging theories.

Many non-science factors bias public and academic thinking toward non-programmed aging theories. For example, most people are trained in Darwin’s mechanics theory as the only science-based theory. Only a tiny fraction of these people are trained in modern population-oriented theories and dependent programmed aging theories or their supporting evidence and logic.

Because they predict that very different biological mechanisms are responsible for aging, programmed and non-programmed theories suggest very different medical research paths could be employed toward treating massively age-related diseases and conditions.

For more on evolutionary mechanics and the case for population-oriented theories and programmed aging theories see:

Evolvability, population benefit, and the evolution of programmed aging in mammals.

Aging Theories Articles Index

Thinking about theories of aging in humans and other mammals in the academic gerontology and more general bioscience community now centers around two concepts: Aging (and an organism-design-limited lifespan) is genetically programmed and an adaptation because limiting lifespan created an evolutionary advantage, or, it is not. Opinions in the gerontology community tend to be highly polarized on this issue.

Thinking about theories of aging in humans and other mammals in the academic gerontology and more general bioscience community now centers around two concepts: Aging (and an organism-design-limited lifespan) is genetically programmed and an adaptation because limiting lifespan created an evolutionary advantage, or, it is not. Opinions in the gerontology community tend to be highly polarized on this issue.